By Catia M. Oliveira1, Amy Atkinson2, Michelle St Clair3, Gareth Gaskell1, Lisa Henderson1

1 University of York, 2 University of Lancaster, 3 University of Bath

Humans spend a large portion of their lives asleep. Whilst this unconscious state leaves us more susceptible to threats, it has been evolutionarily preserved even though there is a high degree of inter- and intra-species individual differences in sleep characteristics. At a lower level, sleep has been found to play a crucial role in our bodily functions from how genes and cells operate as well as its involvement in physiological processes such as immunity and metabolism. At a higher level, sleep has been involved in complex brain functions such as cognition, language and mental health (1,2).

Prior research has shown that sleep enhances our ability to learn and consolidate new information. More specifically, the neural processes that occur during sleep play an important role in memory consolidation, with new information being strengthened and integrated into long term memory networks in the brain such as the neocortex thus enabling generalisation across different contexts (3). Poor sleep has also been associated with poorer academic grades as well as increased likelihood of school absenteeism and dropout (4–6). Importantly, sleep extension studies, which aim to increase sleep duration during the school week, have reported improvements in academic outcomes (7). Sleep issues have also been linked to mental health difficulties, though it is still unclear whether and how sleep is causally related to mental health disorders. In a recent meta-analysis, sleep alterations and continuity were observed in most mental disorders (8).

However, despite the extensive research underlining the importance of sleep, and the high incidence of sleep problems in children under five years of age have sleep difficulties (25-40%; (9)), there is still a very limited understanding as to whether sleep difficulties in the early years have a lasting downstream impact on neurocognitive development, academic achievement, and mental health. This is important because despite the marked changes in sleep across development, preliminary evidence suggests that individual differences in sleep (such as night wakings) that emerge in the first years of life remain stable for several years (10), such that children who are poor sleepers in early childhood are likely to be poor sleepers later in childhood. Whilst there is some evidence showing that childhood sleep problems are concurrently and longitudinally associated with poorer performance in cognitive and academic abilities (11,12), the role of sleep problems in the early years on later vocabulary, school readiness, academic achievement, and mental health is understudied.

In our study, we aimed to fill this critical gap in knowledge, by assessing the stability of sleep over development from 18 months to 9 years via the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) longitudinal dataset, as well as the impact of early sleep (from 18 months to 4 years) on later vocabulary, academic achievement and mental health, particularly anxiety and depression. In this dataset, sleep characteristics were assessed through questionnaires completed by the mother from 6 months (N=11485) to 9 years (N=7882) and by adolescents at 15 years (N=5515).

Our findings revealed that two factors appeared to be important in understanding early years sleep, the first capturing sleep quality (i.e., sleep routine, number of awakenings, sleep behaviours such as getting up after being put to bed, getting up after little sleep) and the second pertaining to sleep timings (i.e., sleep routine, bedtime, wake up time, getting up early). Both of these factors were stable across time (i.e., highly predictive from one time point to the next); but were not so strongly associated with each other at each time point. Therefore, we observed that sleep quality and sleep timing remain stable from infancy to adolescence, suggesting that infants with poor sleep may be at longer term risk for poor sleep in childhood and adolescence. The results also suggest that the development of sleep quality and timing are largely independent, suggesting that each may require different intervention approaches.

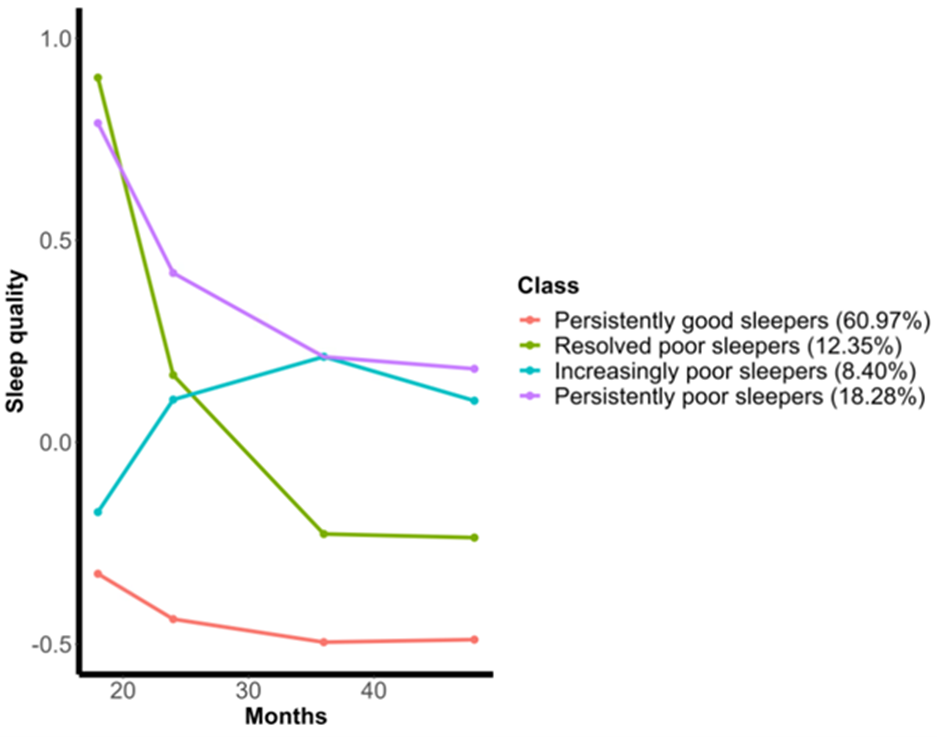

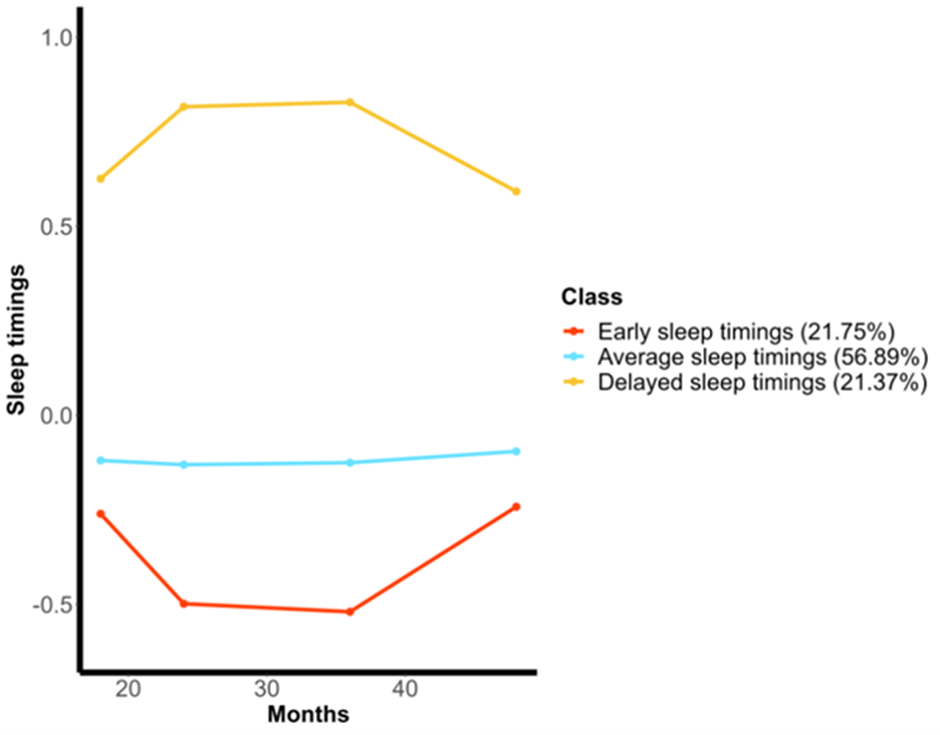

We then explored how early sleep characteristics are linked to vocabulary, academic achievement, and mental health later in life by using growth mixture models. These models allow us to identify distinct sleep growth patterns in our sample. For sleep quality, four distinct groups were identified (Figure 1): persistently good sleepers (60.97%), resolved poor sleepers (12.35%), increasingly poor sleepers (8.40%) and the persistently poor sleepers (18.28%), whilst for sleep timings, three groups were identified (Figure 2): early sleep timings (21.75%), average sleep timings (56.89%) and the delayed sleep timings (21.37%). These profiles were then used to predict later outcomes. We observed that early sleep is associated with later mental health, as children with poorer sleep quality from 18 months to 4 years (persistently poor sleepers and increasingly poor sleepers) and those with delayed sleep timings showed worse mental health outcomes in late childhood and adolescence, specifically, these children were more likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for anxiety and depression than the children in the remaining classes. Persistently poor sleepers and increasingly poor sleepers, as well as those with delayed sleep timings, were also associated with worse outcomes for vocabulary (at 8 and 15 years), school readiness (at 4-5 years) and academic achievement (i.e., school grades across primary and secondary school).

Even though our findings suggest that poor early sleep is associated with worse mental health, vocabulary and academic achievement, it is important to highlight that twin studies have demonstrated that sleep characteristics are influenced by modifiable environmental influences, such as sleep hygiene (13). Furthermore, research suggests a positive impact of sleep interventions in early infancy, which have been found to reduce the number of night wakings and increase nighttime sleep duration (14). Thus, our findings showcase the need for increasing awareness of the importance of sleep across development, as well as the need for timely action when children display sleep problems. For a considerable number of children with sleep problems, these issues might persist across time which may lead not only to negative long lasting outcomes for their development as observed in our study, but also the entire family’s quality of life (15).

Key Takeaways

- Even though prior research has shown that sleep is changeable, in our study we find that, at the group-level, sleep is stable across time;

- Sleep in the early years is associated with vocabulary, academic achievement, and mental health in childhood and adolescence. Those with worse sleep quality and delayed sleep timings are at a higher risk of having poorer vocabulary, as well as worse outcomes for academic achievement and mental health;

- We must ensure that parents and practitioners are aware of the role that sleep plays across development, so that timely action is taken if necessary to avoid the potential negative impacts of poor sleep on later academic and mental health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Sleep quality trajectories. Lower scores on the y axis indicate better sleep quality.

Figure 2.

Sleep timings trajectories. Lower scores on the y axis indicate early sleep timings.

References

1. Knowland VCP, Berens S, Gaskell MG, Walker SA, Henderson LM. Does the maturation of early sleep patterns predict language ability at school entry? A Born in Bradford study. J Child Lang. 2022;49:1–23.

2. Coutrot A, Lazar AS, Richards M, Manley E, Wiener JM, Dalton RC, et al. Reported sleep duration reveals segmentation of the adult life-course into three phases. Nat Commun. 2022 Dec 13;13(1):7697.

3. Tamminen J, Davis MH, Merkx M, Rastle K. The role of memory consolidation in generalisation of new linguistic information. Cognition. 2012 Oct;125(1):107–12.

4. Hysing M, Sivertsen B, Nilsen SA, Heradstveit O, Bøe T, Askeland KG. Sleep and dropout from upper secondary school: A register-linked study. Sleep Health. 2023 Aug;9(4):519–23.

5. Alfonsi V, Scarpelli S, D’Atri A, Stella G, De Gennaro L. Later School Start Time: The Impact of Sleep on Academic Performance and Health in the Adolescent Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Apr 9;17(7):2574.

6. Bauducco SV, Tillfors M, Özdemir M, Flink IK, Linton SJ. Too tired for school? The effects of insomnia on absenteeism in adolescence. Sleep Health. 2015 Sep;1(3):205–10.

7. Gruber R, Somerville G, Bergmame L, Fontil L, Paquin S. School-based sleep education program improves sleep and academic performance of school-age children. Sleep Med. 2016 May;21:93–100.

8. Baglioni C, Nanovska S, Regen W, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B, Nissen C, et al. Sleep and mental disorders: A meta-analysis of polysomnographic research. Psychol Bull. 2016 Sep;142(9):969–90.

9. Byars KC, Yolton K, Rausch J, Lanphear B, Beebe DW. Prevalence, Patterns, and Persistence of Sleep Problems in the First 3 Years of Life. Pediatrics. 2012 Feb 1;129(2):e276–84.

10. Hysing M, Harvey AG, Torgersen L, Ystrom E, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Sivertsen B. Trajectories and Predictors of Nocturnal Awakenings and Sleep Duration in Infants. Behav Pediatr. 2014;35(5):8.

11. Bub KL, Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M. Children’s sleep and cognitive performance: A cross-domain analysis of change over time. Dev Psychol. 2011;47(6):1504–14.

12. Williamson AA, Mindell JA, Hiscock H, Quach J. Longitudinal sleep problem trajectories are associated with multiple impairments in child well‐being. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020 Oct;61(10):1092–103.

13. Mindell JA, Meltzer LJ, Carskadon MA, Chervin RD. Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: Findings from the 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Poll. Sleep Med. 2009 Aug;10(7):771–9.

14. Stremler R, Hodnett E, Lee K, MacMillan S, Mill C, Ongcangco L, et al. A Behavioral-Educational Intervention to Promote Maternal and Infant Sleep: A Pilot Randomized, Controlled Trial. Sleep. 2006 Dec;29(12):1609–15.

15. Teti DM, Shimizu M, Crosby B, Kim BR. Sleep arrangements, parent–infant sleep during the first year, and family functioning. Dev Psychol. 2016 Aug;52(8):1169–81.

About the Author

Catia M. Oliveira

University of York

Catia M. Oliveira is currently working as a Research Associate at the University of York, after completing her PhD in 2022. Catia’s current project aims to understand the downstream effects of preschool sleep for vocabulary, education, and mental health outcomes in the ALSPAC and Born in Bradford longitudinal samples. Her research focuses primarily on typical and atypical language and literacy development in children, including dyslexia and Developmental Language Disorder (DLD), and how language development relates to mental health and other cognitive abilities.