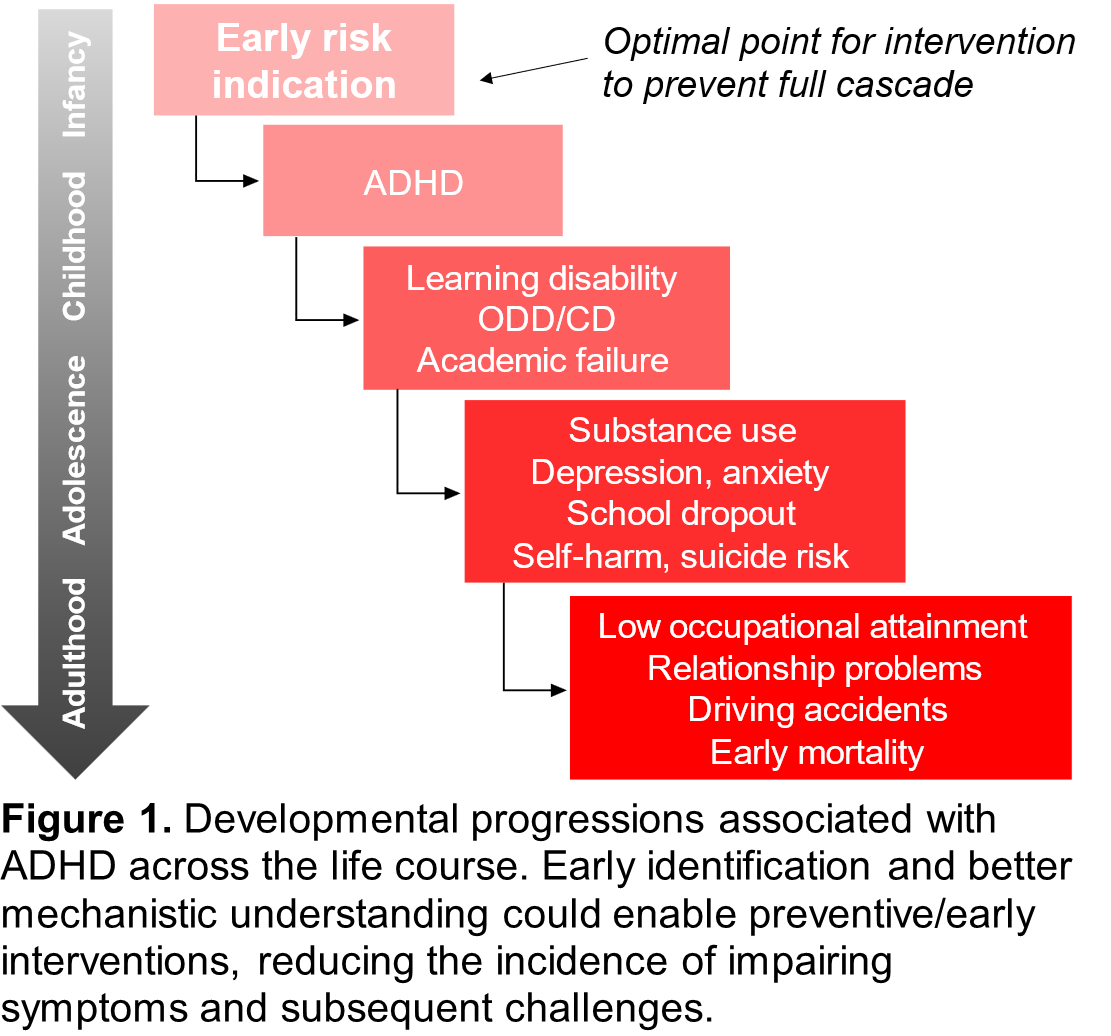

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most prevalent neurodevelopmental condition, affecting ~8% of children in the U.S.1 With an average age of diagnosis of approximately 7 years, by the time it’s typically detected, intervention can already be a challenge. As shown in Figure 1, ADHD portends a host of other, later‐emerging forms of psychopathology and impairment,2 and frequently co‐occurs with learning disabilities, depression, anxiety, oppositional defiant and conduct disorders, and substance use disorders. Long-term impairment into adulthood is common, including relationship problems, lower educational and occupational attainment, driving accidents, self-injury and high rates of suicide attempts, and early mortality.3–5 Because ADHD is usually the first of these to develop6 and may exert a causal influence on later-occurring conditions,7,8 it plays an outsized role in public health. Overall, because of the high prevalence and significant impairment associated with ADHD across the lifespan,3,5,9,10 there’s an urgent need to identify, as early as possible, young children in need of support in order to improve longer-term outcomes.

and substance use disorders. Long-term impairment into adulthood is common, including relationship problems, lower educational and occupational attainment, driving accidents, self-injury and high rates of suicide attempts, and early mortality.3–5 Because ADHD is usually the first of these to develop6 and may exert a causal influence on later-occurring conditions,7,8 it plays an outsized role in public health. Overall, because of the high prevalence and significant impairment associated with ADHD across the lifespan,3,5,9,10 there’s an urgent need to identify, as early as possible, young children in need of support in order to improve longer-term outcomes.

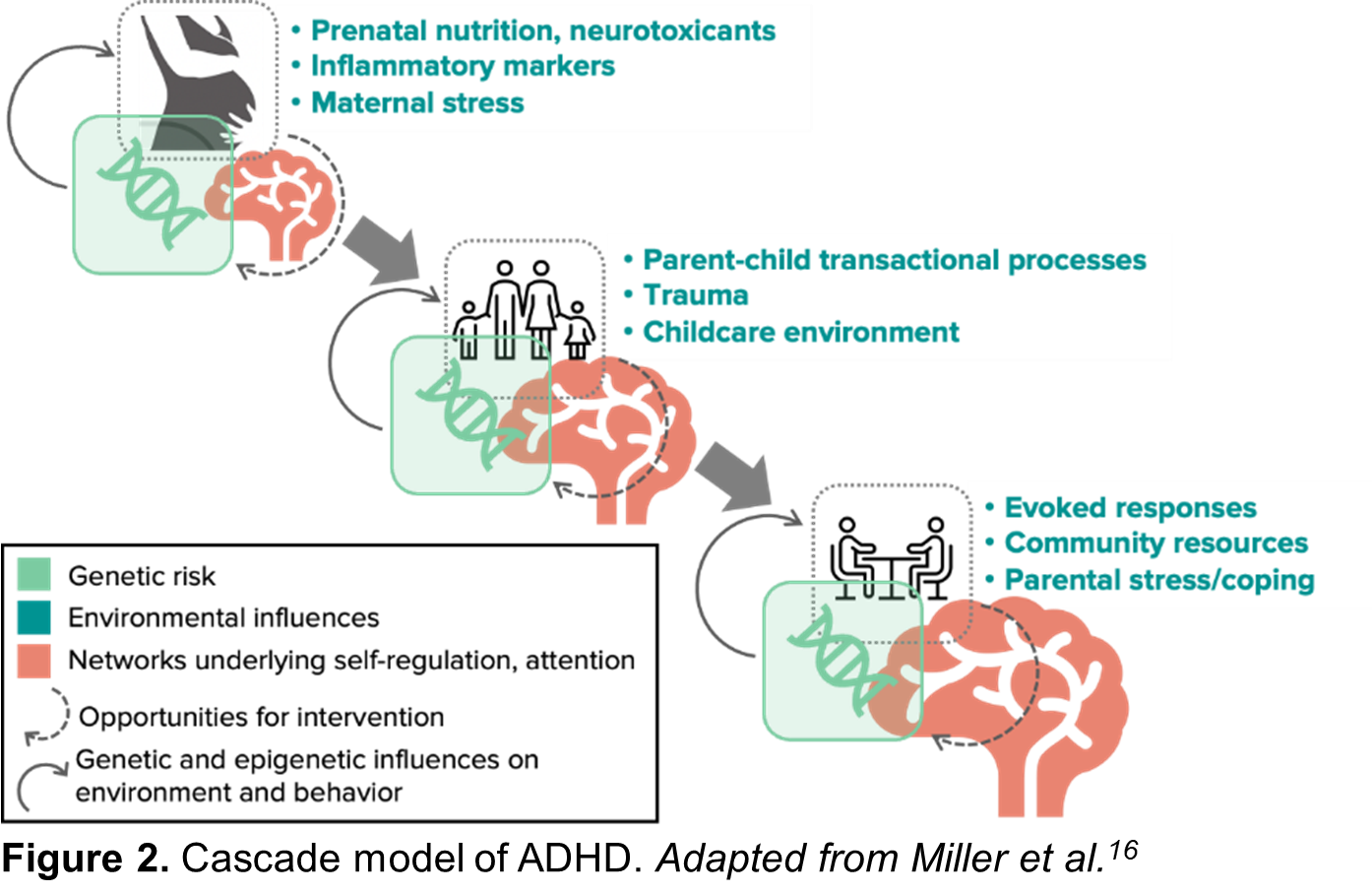

Although it is commonly believed that ADHD originates earlier in development than it is typically diagnosed, there remains some controversy surrounding the idea of diagnosing ADHD in very young children. There are reasonable concerns about medicating young children, over-diagnosis, and differentiating typical from atypical preschooler behavior. Indeed, many of the symptoms of ADHD are expected in young children. The initial research on the early ADHD phenotype focused on the preschool period (3-5 years), and multiple studies have shown that careful, thorough diagnoses in preschoolers persist in the majority of cases.11,12 But in our view, the preschool period is already late! This is because it is increasingly clear that etiological mechanisms associated with ADHD begin to exert effects prenatally, continuing through the infant-toddler period, a time characterized by heightened neural plasticity that could potentially amplify intervention effects. Thus, the mechanisms associated with ADHD act well before the age at which diagnoses can be made and symptoms can be reliably measured with current tools. As such, there is growing scientific interest in methods for identifying infants and toddlers at elevated likelihood for ADHD, with implications for early detection and intervention science. In the cascade model of ADHD shown in Figure 2, we illustrate bidirectional genetic-environmental influences which impact early development of brain networks related to self-regulation and attentional control across gestation and early development, impacting behavioral outcomes. The dashed arrows indicate effects of environment on genetic expression and brain/behavior outcomes, representing potential preemptive intervention opportunities, while solid arrows indicate genetic and epigenetic expression effects which may be harder to moderate.

preemptive intervention opportunities, while solid arrows indicate genetic and epigenetic expression effects which may be harder to moderate.

Prior studies of early markers of ADHD in the infant-toddler periods generally highlight associations between non-specific factors and later ADHD symptoms like early motor and language delays, as well as temperament differences such as parent-reported overactivity. In 2022, Dr. Elizabeth Shephard published a meta-analysis in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry13 and synthesized the existing literature focused on early life (<5 years) neurocognitive and behavioral precursors of ADHD prior to the preschool period. This meta-analysis revealed significant associations between ADHD and poorer motor and language development, social and emotional difficulties, early regulatory and sleep problems, sensory atypicalities, elevated activity levels, and executive function difficulties. These findings were critically important. They also revealed a number of gaps in the science and a need to remedy some of the methodological issues plaguing the existing literature. For example, studies have mostly been conducted in samples in which diagnostic outcomes had not been characterized, or samples not selected for elevated likelihood for ADHD, with some notable exceptions. The vast majority also relied on retrospective methods, using data from studies that were not originally designed to evaluate these questions, substantially limiting the availability of relevant measures. To remedy these limitations, we have begun using prospective methods to study these questions.

One of the primary designs utilized in early detection research is a familial likelihood design, which focus on recruiting infants at elevated and average likelihood for ADHD based on family history (i.e., presence or absence of first-degree relative with ADHD) so that the sample is enriched for the outcome of interest. Our groups typically enroll participants during gestation or through the first year of life and then follow them prospectively over the course of several years, collecting a variety of different types of data at each age and making initial clinical best estimate outcome determinations at the final study visit. This way, we can look backward at the previously collected data based on outcome group to determine when in development and in what domains the infants who went on to develop high levels of ADHD symptoms differ from those with typical development. Key findings across our groups thus far include:

- Infants at elevated familial likelihood for ADHD exhibit higher levels of ADHD-relevant behaviors (i.e., inattention/distractibility, hyperactivity, impulsivity) by 12 months of age compared to infants at average likelihood when rated by examiners or measured via second-by-second behavioral coding. Parents of infants in the ADHD-likelihood group are also more likely to endorse behavior concerns than parents of infants at average likelihood at 12 months of age, with increasing concerns from 12 to 18 months of age, versus stable concerns in the low-likelihood group.14

- Infants developing high levels of preschool ADHD symptoms are less likely to orient when their name is called at 12 and 18 months of age relative to infants without elevated ADHD symptoms in the preschool period, suggesting the possibility of early differences in attentional orienting mechanisms.15

- The interaction between negative emotionality and cognition measured at 9 months of age predicts toddler ADHD-related behaviors. Specifically, high or low levels of both negative emotionality and cognition predicted more ADHD-related behaviors in toddlerhood, suggesting there may be two affective-cognitive pathways to early inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity.16

- Parent and observer ratings of activity level (but not attention) in 10-month-old infants with a family history of ADHD are positively associated with later preschool ADHD traits at 3 years.17

- 10-month-old family history infants show a lower EEG theta-beta power ratio than infants with no family history and this is positively associated with temperament dimensions conceptually related to ADHD at 2 years.18

- Infants with a family history of ADHD exhibit increased negative affect at 6 months of age. Thus affective response at 6 months of age may provide an early indicator of ADHD liability.19

- Several novel biomarkers of offspring ADHD risk can be assessed prior to the child’s birth, including maternal concentrations of inflammatory cytokines,20 metabolic hormones (adiponectin and leptin),21 and serotonin system metabolites during pregnancy. For example, maternal inflammation in the 3rd trimester predicts child ADHD symptoms at age 4-6 years and mediates the effect of prenatal distress on child ADHD. Thus, maternal prenatal inflammation may be one common pathway by which prenatal risk factors (maternal distress, increased adiposity and poor nutrition) influence offspring mental health outcomes.20

- Prenatal and postnatal factors interact in the prediction of child ADHD risk. For example, increased inflammation during pregnancy is prospectively associated with increased toddler ADHD symptoms, but only when children experience lower levels of maternal sensitivity during infancy.

Overall, we are learning that there is greater potential for earlier detection of ADHD-relevant behaviors than previously possible. But to move the field forward, we recognize that there is a need for collaborative, multisite studies focused on the early ADHD phenotype. To that end, we, along with other colleagues around the world, joined together to form the Early ADHD Consortium. This international network of investigators is engaged in prospective, longitudinal studies of elevated likelihood for ADHD beginning early in life. We are linked by our focus on developmental frameworks and centering developmental trajectories in our work, and through our incorporation of multimethod approaches. Our various teams have different areas of expertise, such as EEG, eye-tracking, behavioral and clinical methods, and preemptive intervention design. We published our first paper reviewing the state of the science and introducing the consortium in 2023 in JCPP Advances,22 and include a list of the measures used by our groups in case other investigators are interested in doing similar work. We are excited about opportunities to come together to pool data, resources, and ideas to increase the impact of this work.

References

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Blumberg SJ. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2018;47(2):199-212. doi:10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860

- Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK. Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults With childhood ADHD: A prospective study. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):637-644. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2354

- Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, Mortensen PB, Pedersen MG. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. The Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190-2196. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61684-6

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, et al. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(7):2693-2698. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010076108

- Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, et al. Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(1):27-41. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9658-z

- Kessler RC, Adler LA, Berglund P, et al. The effects of temporally secondary co-morbid mental disorders on the associations of DSM-IV ADHD with adverse outcomes in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Psychol Med. 2014;44(8):1779-1792. doi:10.1017/S0033291713002419

- Riglin L, Leppert B, Dardani C, et al. ADHD and depression: investigating a causal explanation. Psychol Med. 2021;51(11):1890-1897. doi:10.1017/S0033291720000665

- Treur JL, Demontis D, Smith GD, et al. Investigating causality between liability to ADHD and substance use, and liability to substance use and ADHD risk, using Mendelian randomization. Addiction Biology. 2021;26(1). doi:10.1111/adb.12849

- Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003-2011. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(1). doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001

- Wilens TE, Martelon M, Joshi G, et al. Does ADHD predict substance-use disorders? A 10-year follow-up study of young adults with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(6):543-553. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.021

- Lahey BB. Three-year predictive validity of DSM-IV attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children diagnosed at 4-6 years of age. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):2014-2020. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2014

- Riddle MA, Yershova K, Lazzaretto D, et al. The Preschool Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment Study (PATS) 6-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(3):264-278.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.12.007;

- Shephard E, Zuccolo PF, Idrees I, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: The science of early-life precursors and interventions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2022;61(2):187-226. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2021.03.016

- Miller M, Iosif, A., Bell, L.J., et al. Can familial risk for ADHD be detected in the first two years of life? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2021;50(5):619-631.

- Hatch B, Iosif AM, Chuang A, de la Paz L, Ozonoff S, Miller M. Longitudinal differences in response to name among infants developing ASD and risk for ADHD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2021;51(3):827-836. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04369-8

- Joseph HM, Lorenzo NE, Wang FL, Wilson MA, Molina BSG. The interaction between infant negative emotionality and cognition predicts ADHD-related behaviors in toddlerhood. Infant Behavior and Development. 2022;68:101742. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2022.101742

- Goodwin A, Hendry A, Mason L, et al. Behavioural measures of infant activity but not attention associate with later preschool ADHD traits. Brain Sciences. 2021;11(5):524. doi:10.3390/brainsci11050524

- Begum‐Ali J, Goodwin A, Mason L, et al. Altered theta–beta ratio in infancy associates with family history of ADHD and later ADHD‐relevant temperamental traits. Child Psychology Psychiatry. 2022;63(9):1057-1067. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13563

- Sullivan EL, Holton KF, Nousen EK, et al. Early identification of ADHD risk via infant temperament and emotion regulation: A pilot study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56(9):949-957. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12426

- Gustafsson HC, Sullivan EL, Battison EAJ, et al. Evaluation of maternal inflammation as a marker of future offspring ADHD symptoms: A prospective investigation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;89:350-356. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.019

- Sullivan EL, Molloy KR, Dunn GA, et al. Adipokines measured during pregnancy and at birth are associated with infant negative affect. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2024;120:34-43. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2024.05.018

- Miller M, Arnett AB, Shephard E, et al. Delineating early developmental pathways to ADHD: Setting an international research agenda. JCPP Advances. 2023;3(2):e12144. doi:10.1002/jcv2.12144

About the Author

Meghan Miller

University of California, Davis

Meghan Miller, Ph.D. is a Professor and Vice Chair of Psychology in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences and the MIND Institute at the University of California, Davis. She received her Ph.D. in Clinical Science from the University of California, Berkeley in 2013 and is a licensed clinical psychologist. Her current research is focused on understanding commonalities and differences in early markers of autism and ADHD, along with contextual factors that may interact with genetic likelihood for these conditions.

Tony Charman

King’s College London

Tony Charman, Ph.D. is Emeritus Professor of Child Clinical Psychology at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK. His research aims to better understand development and mental health in autism and the clinical application of this work via screening, diagnostic, intervention and family history studies.

Hanna Gustafsson

Oregon Health & Science University

Hanna Gustafsson, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). She is also a faculty member at the OHSU Center for Mental Health Innovation. Her research explores the impact of prenatal and early life stress on children’s risk for psychopathology, with a focus on psychobiological and family-level mechanisms through which experiences very early in life influence children’s long-term functioning.

Emily Jones

Birkbeck, University of London

Emily Jones, Ph.D. is Professor at Birkbeck, University of London and the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK. Her research interests center on understanding the cognitive and neural mechanisms that drive variability in developmental trajectories.

Heather Joseph

University of Pittsburgh

Heather Joseph, D.O. is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh. She obtained her medical degree at Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine in 2011 and is a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist. Her primary areas of research are the identification of early cognitive and neural signals of inattention as well as the development of behavioral interventions to mitigate the risk of impairment associated with ADHD symptoms in early childhood or parental ADHD.

Elinor L. Sullivan

Oregon Health & Science University

Elinor L. Sullivan, Ph.D. is a Professor in the Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). Dr. Sullivan received her Ph.D. in Physiology from OHSU in 2006 and postdoctoral training at the University of California San Francisco and OHSU. Her research focuses on examining the influence of environmental factors such as nutrition and stress on maternal physical and mental health and on offspring neurobehavioral regulation.