Recently, I was describing my research on kinship terms to a friend, and how in Chinese culture, we never ever call anyone older than us by their given names. As I was explaining this custom, I suddenly realized that I could not remember my maternal grandfather’s name! She looked shocked. I meekly tried to explain that everyone in my generation called him Ah Gong, meaning ‘grandfather’; we never used his given name. Even now, 5 months after this exchange, I still have not been able to remember.

Knowing how to name people appropriately is one of the first things families teach their children, and reflects the concept of language socialisation (Kurniawati et al., 2021) – it lies at the intersection of social cognition and language development. While names that children address their parents with tend to be some of the earliest words acquired by infants (cf. Wordbank), languages differ in the conceptual structures encoded in kinship terminology, as well as practices for naming and address. For example, Mandarin kinship terms for children not only specify the generation and gender, but also relative birth order (e.g., 大姐 da4jie3 ‘big older sister’, 二哥 er4ge1 ‘second older brother’. Indeed, the audience this poster attracted at ICIS were mostly people with Asian heritage – from India, the Philippines, Taiwan etc. – and all of them immediately understood the context of how, unlike Westerners, there are many contexts in which Asians rarely if ever hear given names [see also Kinbank (Passmore et al., 2023), a database of over 200,000 kinterms consolidated from more than 1,200 spoken languages globally].

Given this cross-cultural variation, it remains an open question how multilingual communities socialise their children into culturally appropriate naming customs. In Singapore for instance, English is the main language of business and education, with 86.8% of people reporting speaking English alongside one or more of Singapore’s other official languages (Mandarin Chinese, Malay and Tamil; Singapore Department of Statistics, 2020). How do Singaporean parents teach their children to name their family members?

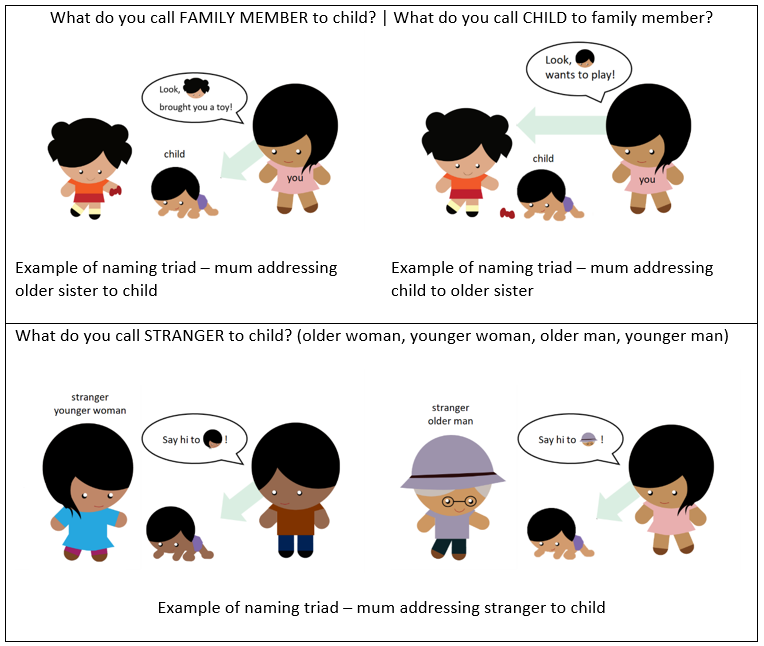

To help answer this question, 86 Singaporean families (ethnicity split: 40 Chinese, 35 Malay, 11 Indian) with children under the age of 4 years participated in an online survey with audio recording questions delivered via Qualtrics with Phonic.ai integration (an app that allows people to collect audio responses in surveys). We asked the parents of these families to report on how parent, sibling, and grandparent figures their child sees regularly are referred to in conversations with the child, as well as how the child is referred to in conversations with each family member. An example set of questions using ‘older sister’ as the target family member are depicted below. As a bonus question, we also asked about the term of address for strangers.

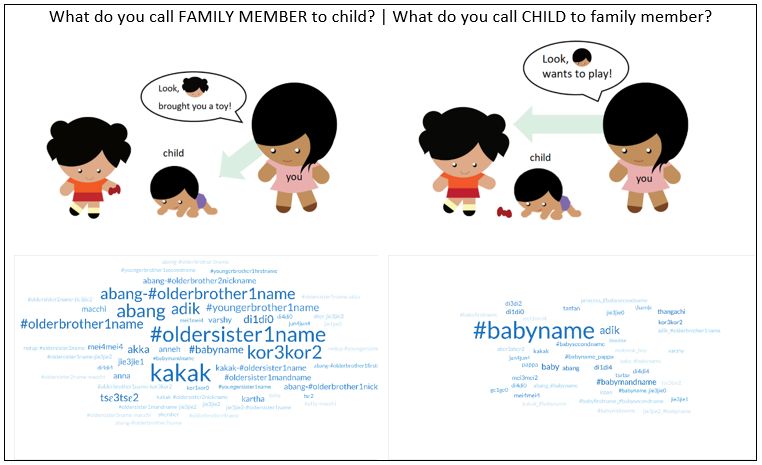

We found that when talking with their child about any adult (parent, grandparent), parents use child-centred relational terms (i.e., terms in which the younger family member would use to address the older family member; Dickey, 1997, Morita, 2003). Interestingly, only Chinese families included maternal/paternal information for grandparents; Malay and Indian families do not have words in their languages that mark this so distinctly. For example, Mandarin terms for maternal grandmother 外婆 wai4po2 and grandfather 外公 wai4gong1 have the 外 wai4 prefix, meaning ‘external’, i.e., external to the paternal line of descendents! (There are other terms that our participants used in this study; I highlight only this example.) It is heartening to note that, while probably not being very ‘traditional’ in the strictest sense of the word, the majority of Chinese families nowadays, or at least those in this study, used more neutral terms that do not distinguish maternal/paternal lines for all grandmothers/grandfathers. When talking about siblings, child-centered relational terms are used selectively when referring to older children in conversations with younger children (for example, ‘older sister’ versus ‘Sarah’), perhaps to further socialize the practice of using relational terms rather than proper names for elders. By contrast, when talking about their younger child John to someone older (grandparents, parents and older siblings), parents often use given names rather than relational terms (‘John’ versus ‘younger brother’/’little boy’).

Translations of some of the words in the word clouds:

Chinese languages: jie3jie1 (older sister, Mandarin), kor3kor2 (older brother, Cantonese though not typical Cantonese tones), mei4mei4 (younger sister, Mandarin), di4di0 (younger brother, Mandarin)

Malay: kakak (older sister), abang (older brother), adik (younger sibling)

Tamil: akka (older sister), anneh/anna (older brother), thangachi (younger sister), paapa/pappa (child)

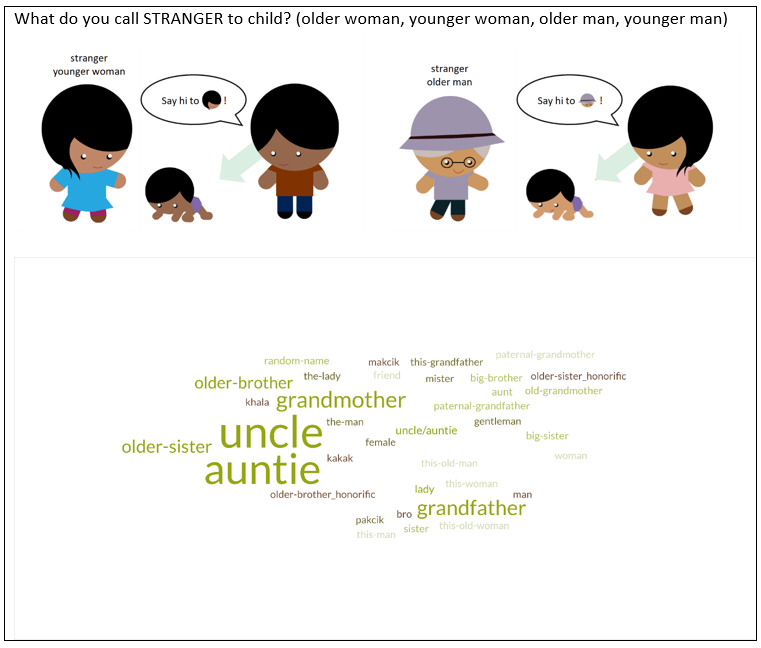

In sum, early socialisation encodes the importance of using relational terms to refer to people who are older, but not younger, including when the referred-to individual is only slightly older (e.g., in the same generation as the child). We also learned that parents in Singapore (and I bet many other places too) also often use relational terms (‘uncle’, ‘auntie’) as generic names for strangers (no matter whether they are older or younger than the parent):

As the year draws to a close, I hope that everyone is surrounded by people who make them feel like family.

Final note: As one of the ICIS Communications Committee members, I would also like to thank everyone for engaging with our posts on Bluesky, X/Twitter, LinkedIn (here and here), TikTok, Instagram and YouTube. Happy holiday season, see you in 2025!

Acknowledgements: With eternal gratitude to

- Dr Suzy Styles for your guidance in All of the Things and for being with me on this Glasgow trip.

- Jin Yi Loh (Mandarin), Xavier Ler (Mandarin), Shaza binte Amran (Malay), Vinitha Selvarajan (Tamil) and Sheetal Sahana Vimalraj (Tamil) for assisting with transcription of family terms.

- Shaza binte Amran and Kelly Si Ning Choo for assistance with family scenario images.

References

Choo, R. Q. & Styles, S. J. (2024). Kinship terms of address and reference among families in Singapore. Poster presented at the International Congress of Infant Studies, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, 8-11 July 2024. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4FR52

Dickey, E. (1997). Forms of Address and Terms of Reference. Journal of Linguistics, 33(2), 255–274. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4176417

Kurniawati, W., Suhandano, S. & Kushartanti, B. (2021). Language socialization in family environments through terms of address to children. Litera, 20(2), 250–268. https://doi.org/10.21831/ltr.v20i2.39455

Morita, E. (2003). Children’s use of address and reference terms: Language socialization in a Japanese-English bilingual environment. Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication, 22(4), 367–395. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.2003.019

Passmore, S., Barth, W., Greenhill, S. J., Quinn, K., Sheard, C., Argyriou, P., et al. (2023). Kinbank: A global database of kinship terminology. PLoS ONE, 18(5): e0283218. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283218

Singapore Department of Statistics. (2020). Census of Population 2020: Key Findings. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/cop2020/sr1/findings.pdf

About the Author

Rui Qi Choo

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Rui Qi Choo (first name is two words, pronounced like ‘Ray [of sunshine] Chee[se]’, last name is like the choo-choo train), PhD is a Research Fellow at the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore and Associate Faculty at the Singapore University of Social Sciences. She is a developmental psycholinguist who is interested in anything child-related, language-related, and Singapore-related. Her research has mostly looked at how children learn to speak, read and write in their languages in multilingual translanguaging Singapore. She also teaches Developmental Psychology and bilingualism-related modules at SUSS. Rui Qi is one of the ICIS Communications Committee members: she curates posts for Bluesky, X and LinkedIn (look out for her emails asking you for a blurb of your paper) and is part of the Instagram team turning Baby Blog posts into parent-friendly slides. She dabbles in doodling, Chinese calligraphy and making kasut manek (beaded shoes – she just completed her first pair!) when she’s not chipping away at her research data or teaching. She can be found on Bluesky, X/Twitter and LinkedIn.