by Laia Fibla, Jessica E. Kosie, Ruth Kircher, Casey Lew-Williams, and Krista Byers-Heinlein

Baby Sophia hears Spanish from her mother and Catalan from her father. Baby Andreas hears English from his mother, German from his father, and French at daycare. Baby Jayden hears English and Mandarin from both of his dads, and hears Hokkien from his grandmother. These babies are examples of the millions of children around the world who grow up bilingual in diverse contexts, learning two or more languages from early in life (Wei, 2000). Early bilingualism is linked to benefits across many different domains (e.g., Bialystok, 2018). Supporting the bilingual development of babies like Sophia, Andreas, and Jayden is essential, as early language development predicts later language skills, cognitive abilities, and school achievement (e.g., Schwab & Lew-Williams, 2016).

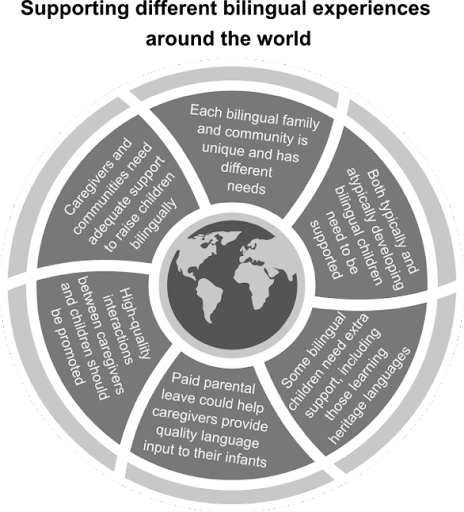

Even though much of early language transmission occurs in the home with caregivers, policymakers and communities play an essential role in supporting bilingual babies’ language learning. Recent research from a variety of domains – including psychology, linguistics, and education – provides a solid scientific foundation for creating policies that support successful bilingualism. Our recent article highlights six main implications for policy, which are also summarised on the pinwheel below (also available at https://osf.io/zbm36/).

- Caregivers and communities need public support to raise their children bilingually.

Caregivers – and communities more broadly – need to be empowered to raise children with multiple languages from infancy if they so desire. Spread the word about the long-term, positive outcomes of the intergenerational transmission especially of Indigeneous and immigrant heritage languages – that is, languages other than the one(s) of the wider community. Develop tailored, community-based programs. For example, the “Sacred Little Ones” program develops early childhood education projects tailored to Native American communities, promoting languages and culture.

- Encourage high-quality interactions between caregivers and their children.

Language learning is linked to the quality of language that infants and children hear, and bilingual children need to have lots of high-quality experiences in each of their languages. High-quality interactions are rich with language and interactions between a caregiver and the child. Child-directed speech, which is high-pitched and melodic, is especially beneficial to language learning. In bilingual families, high-quality interactions can include language switching, where a speaker changes languages during a conversation, either within a sentence or between sentences. Studies indicate that parents often use language switching strategically to boost their children’s understanding and teach them new words.. Further, reading to children is a great way to expose them to multiple languages in an interactive way. For example, Storybooks Canada is a free online resource, which provides culturally diverse stories with text and/or audio in over 30 languages, including many Indigenous and immigrant heritage languages.

- Paid parental leave can help primary caregivers provide more frequent high-quality language experiences to their bilingual infants.

Young bilinguals’ development will benefit from policies that allow key caregivers to spend more time with their infants during the first years of life. Some countries, such as Canada and Sweden, offer policies that promote the sharing of family leave between both parents, which can help ensure that bilingual children get sufficient rich exposure to all of their home languages. This is particularly important within Indigeneous and heritage language families, where parents often provide children’s main exposure to a language.

- Children learning Indigenous and immigrant heritage languages might need extra support.

It can be challenging for children to gain sufficient high-quality experiences in languages that are spoken less widely in the community, such as Indigeneous and immigrant heritage languages. Making childcare available in multiple languages can help support families’ language choices and children’s bilingual development. Nursery or preschool programs could expose children to diverse languages, not only to support language learning but also to promote positive attitudes and related cultural knowledge. Targeted playtimes or storytimes in cultural centres and public libraries help support social networks among families that share the same language(s). Those institutions can provide useful resources, such as children’s books in different languages and in bilingual formats. There are lots of great examples worldwide. “REFORMA” in the U.S. promotes Spanish-English bilingualism and biculturalism by making more books in Spanish available in libraries. The New York Public Library provides both recorded and live storytimes in a variety of languages, including Japanese and Spanish. In Singapore, the Early READ Programme from the National Library Board offers storytime livestream sessions and online resources in multiple languages such as English, Chinese, Malay, and Tamil. Multilingual storytime initiatives are also common in libraries in Israel.

- Bilingualism needs to be supported in both typically and atypically developing children.

Bilingualism does not cause language impairments or developmental delays. Nonetheless, unrelated to their language backgrounds, some children face special developmental challenges such as Autism Spectrum Disorder or Down Syndrome. Early education policies need to address bilingual language learning in children with diverse needs, and give access to clinical and educational services in all the child’s languages. Clinical evaluations must take into account bilingual children’s full, diverse language achievements, and bilingual children should not be assessed in the same way as monolingual children. Whenever possible, evaluations should be conducted by trained professionals who are knowledgeable about bilingual assessment, and (if possible) who are fluent in each of the child’s languages.

- Each bilingual family and community is unique and has different needs.

One of the challenges in creating policies that support bilingualism is the substantial variability in the experience of bilingual children. Different children hear different languages, and languages are used in different ways across diverse bilingual households including who speaks different languages around them and how the languages are used. This means we need to develop policies that can be adapted to each child’s context and family needs, to be able to support diverse family structures across the globe.

Overall, scientific research shows that children’s success in learning each of their languages is a direct consequence of the quality of their everyday language experience, including at home, in daycare and preschools, and in the broader community context. This has implications for policy making. Moreover, we can see that Sophia, Andreas, and Jayden have very different experiences with bilingualism: there are arguably as many ways to grow up bilingual as there are bilingual children. To promote successful bilingual development, we need policies that acknowledge this variability and support frequent exposure to high-quality experiences in each of a child’s languages.

About the Authors

Laia Fibla

Concordia University

Laia Fibla is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Concordia Infant Research Lab. Her research focuses on the role of children’s everyday experiences on their language learning skills. She is particularly interested in studying this relationship across bilingual communities as well as across different cultures and languages.

Jessica E. Kosie

Princeton University

Jessica Kosie is an NIH Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Princeton Baby Lab. She is interested in how infants’ everyday experience varies across families, communities, and cultures, with a focus on communicative interactions between caregivers and infants. She prioritizes open science in her research and teaching, co-leads the ManyBabies 5 project, and serves as the co-organizer of the DARCLE Pre-PI group.

Ruth Kircher

Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning

Ruth Kircher is a researcher at the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning, which is part of the Fryske Akademy in Leeuwarden (Netherlands). She is a sociolinguist with a specialisation in societal multilingualism; her research focuses on language attitudes and ideologies, language practices, and language policy and planning – especially in relation to autochthonous and migrant minorities.

Casey Lew-Williams

Princeton University

Casey Lew-Williams is a professor in the Department of Psychology at Princeton University. He directs the Princeton Baby Lab, where his students and postdocs study how babies learn, with a focus on language and communication. His current work is funded by the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Behavior and by Wellcome Leap. He is a co-chief editor of Frontiers for Young Minds and a co-founder of ManyBabies.

Krista Byers-Heinlein

Concordia University

Krista Byers-Heinlein is a Professor of Psychology at Concordia University, where she holds the Concordia University Research Chair in Bilingualism and Open Science and leads the Concordia Infant Research Lab. Her research investigates the language, cognitive, and social development of bilingual infants and toddlers. She is committed to open science, and led the ManyBabies 1 Bilingual project.