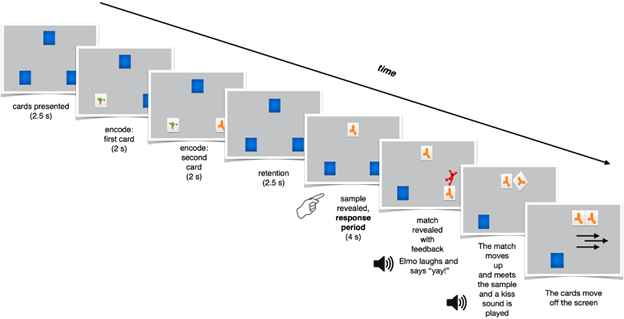

Across four preregistered experiments, we had 1.5- to 8-year-olds play a card-matching game on a tablet or video screen (see Figure 1). The game consisted of three face-down cards that “fly” in. There were two cards on the bottom and one on the top. Each of the two bottom cards flipped over to reveal an image. Then, they flipped face down. Finally, the top card flipped over to reveal a match with one of the two bottom cards. It is there that we looked to see whether children looked at (1.5- to 2.5-year-olds) or tapped (3- to 8-year-olds) the correct matching card. There are four trials of this card-matching game where the images on the cards are all unique, and four trials where the images on the cards are repeated from trial to trial. In this repeated condition, the first trial may have an orange on the left card and a banana on the right card. The second trial may then have the orange on the right and the banana on the left. If toddlers and young children are affected by proactive interference, then on later trials, they may have more trouble picking out which side the matching card was on in the repeated condition compared to the version where they see all new cards in each trial.

Figure 1. The sequence of events in a test trial for the card-matching game.

So how do children do? Our first study2 using this card-matching game across three preregistered experiments (N = 245, 111 boys) found that 2.5- to 8-year-old children will, like you, walk to yesterday’s parking spot instead of today’s. Our fourth preregistered experiment3, tested 1.5- to 2.5-year-olds (N = 34) and found that toddlers also make more memory mistakes when old information (“the orange was on the left last time…”) can interfere with new information (“was the orange on the left or the right this time?”). This may not sound too surprising, as we all know that children make much bigger (and funnier, at times) memory mistakes than getting mixed up in a card-matching game. We indeed expected that children, especially young toddlers, would be more susceptible to something like proactive interference than older children or adults. What’s important about quantifying this is that most measures of memory performance in children and toddlers don’t take proactive interference into account, and thus may be reporting children’s memory as worse than it really is.

Plenty of laboratory and clinical tasks measuring memory performance in toddlers and children involve repeated trials where children have to remember the same or similar information over and over again4,5,6. Although this is an intuitive way to get an average memory “score”, if children’s memory is disproportionately affected by proactive interference, then their performance will tend to decline across trials and thus lead to an underestimation of their actual memory abilities. For example, in our card-matching game, children must remember (1) the image on the bottom-left card, (2) the image on the bottom-right card, and after they see the top card and need to choose the match, they need to remember (3) where (right or left) the matching card was. Previous work has shown that by 9 months of age, infants can keep track of “what” went “where” for two objects at a time7. Yet when we induce proactive interference in our experiment, 1.5- to 2.5-year-olds’ performance drops to chance level at this “what” went “where” task by the 4th trial.

It comes as no surprise that toddlers’ working memory would be sensitive to interference effects. Our research has the following takeaway: through critically assessing old assumptions, we can come to new conclusions that impact how future research is conducted. This is the beauty of scientific progress, and it wouldn’t be possible without the R15 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) we received to help pay for equipment and reimbursing the hundreds of families who volunteered their time to participate in our research. Federal grants not only provide financial stability to research projects, but they also buy time. An awarded NIH grant allows researchers to spend time training and mentoring the future generation of scientists. For example, the current project is co-led by an undergraduate research assistant, Zane Mourad, who is not only a co-author on this blog post, but they are also being fully immersed in research thanks to the time that grants allow faculty and graduate students to train mentees. Therefore, only through this kind of major funding could we tackle our next questions: are some kids more susceptible to proactive interference than others? If so, do cognitive assessments appropriately take this into account? We hope to continue our research into children’s memory and forgetting.

- Hamilton, M., Ross, A., Blaser, E., & Kaldy, Z. (2022). Proactive interference and the development of working memory. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews – Cognitive Science, 13(3), e1593.

- Hamilton, M., Roper, T., Blaser, E., & Kaldy, Z. (2024). Can’t get it out of my head: Proactive interference in the visual working memory of 3- to 8-year-old children. Developmental Psychology, 60(3), 582–594.

- Koolhaas, C., Hamilton, M., Roper, T., Blaser, E., Kaldy, Z. Proactive interference disrupts 2-year-olds’ working memory. Poster presentation at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, May 1 – May 3, 2025, Minneapolis, MN.

- Fitzpatrick, C., & Pagani, L. S. (2012). Toddler working memory skills predict kindergarten school readiness. Intelligence, 40(2), 205-212.

- Morra, S., Gandolfi, E., Panesi, S., & Prandelli, L. (2021). A working memory span task for toddlers. Infant Behavior and Development, 63, 101550.

- Willoughby, M. T., Blair, C. B., Wirth, R. J., & Greenberg, M. (2010). The measurement of executive function at age 3 years: psychometric properties and criterion validity of a new battery of tasks. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 306.

- Kaldy, Z., & Leslie, A. M. (2003). Identification of objects in 9‐month‐old infants: integrating ‘and ‘information. Developmental Science, 6(3), 360-373.

About the Author

Candice Koolhaas

PhD Student at UMass Boston

Candice’s background as an early childhood educator, combined with her interest in cognitive development in her research with Dr. Kaldy, where she uses eyetracking to study working memory and cognitive effort in toddlers up to adults.

Bluesky: @ckoolh.bsky.social

Personal website: https://candicekoolhaas.github.io/

Zane Mourad

Research Assistant at UMass Boston

Zane is an undergraduate student working in the UMass Boston Early Minds Lab under the supervision of Dr. Kaldy and Candice, studying proactive interference and working memory in infants.

CV: link

Zsuzsa Kaldy

Professor at UMass Boston

Zsuzsa’s research focuses on the early development of visual attention and working memory in young children. What kind of information do infants encode about objects, and what do they remember about them? Recently, she has been interested in how children use their working memory in naturalistic settings.

Bluesky: @zsuzsakaldy.bsky.social